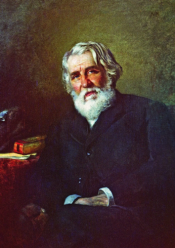

Ivan Turgenev: "I want truth, not salvation"

November 9, 2020 marks 202 years since the birth of Ivan Sergeevich Turgenev (1818-1883), the leading figure of Russian literature. Marking his 200th anniversary, the Presidential Library presented the richest collection “Ivan Turgenev", which spotlights not only electronic copies of the author's works, but also articles and memoirs about him, correspondence: "Critical articles about Ivan Turgenev and Leo Tolstoy" by N. Strakhov (1885), "Ivan Turgenev in the memoirs of the revolutionaries of the seventies" (1930), "Letters of Ivan Turgenev to Pauline Viardot" (1900), etc.

The future writer was born in Orel, in the family of a captain-cuirassier, who married the owner of the Spasskoye-Lutovinovo estate of the Mtsensk district. “This marriage was not one of the happy ones”, - notes Alexander Smirnov. "Turgenev's mother...personified that intoxication with power, which was created by serfdom... <...> "They beat me up", - Turgenev said, "for all sorts of trifles almost every day". The child was lonely, he liked the forest, fishing, going out to the night with peasant children.

Starting to write, being a student first at Moscow, then at St. Petersburg universities, Turgenev quickly acquired a name in literature. The story in verse "Parasha", published in 1843, immediately attracted attention, especially after Belinsky's response, who outlined the main thing in the novice author: "Style in a poem - critic Evgeny Solovyov quotes in the publication “Ivan Turgenev", (1919), - reveals extraordinary poetic talent; and faithful observation...graceful and subtle irony, under which so many feelings are hidden - all this shows in the author...the son of our time, who carries in his chest all his sorrows and his questions. We are not talking about originality: it is the same as talent - at least without it there is no talent".

After attending a Pauline Viardot concert in 1843 and hearing one of the best mezzo-sopranos in Europe, the young writer was deeply impressed by both the manner of singing and the performer herself. Since then, meetings and partings with Viardot, either at home or in Europe, have become the fate of Turgenev. Their relationship lasted 40 years - until the writer's death. Frequent partings led to a long-term epistolary romance between the singer and the writer, which was captured in the published “Letters of Ivan Turgenev to Paulina Viardot” (Viardot allowed to publish several of her letters to Ivan Sergeevich only after her death).

Already from one of the first letters, it is clear how much the meeting “touched” the writer: “...apparently, I am destined to be happy if I deserve that the reflection of your life mingles with mine! As long as I live, I will try to be worthy of such happiness; I began to respect myself since the time I carry this treasure in me". In the letters to Viardot during the first years of the correspondence, one can hear an understandable desire of a novice writer to become on a par with a woman who has reached universal worship: "Do you know, madam, that your lovely letters pose a very difficult job for those who claim the honor of corresponding with you?" - he writes in a letter dated October 19, 1847. Here she notes her "mind, so simple and so serious in its subtlety and charm

Over time, this correspondence became more and more necessary for both. And the problems that were raised in it already went beyond the warm welcome messages. In his letters, Turgenev spoke with Viardot about the most important thing: “Whatever atom I am, I am my own master; I want truth, not salvation; I drink it from my mind, and not from grace…", - we read in the publication "Letters of Ivan Turgenev to Pauline Viardot".

The rivalry between two beautiful, talented people (although many did not find Viardot attractive), constantly exchanging creative intentions in letters, bore fruit. The writer will find a fruitful creative environment, heartfelt warmth, being in close communication with the Viardot family - since 1847, Turgenev lived for a long time in France, in Baden-Baden, on the outskirts of Paris.

Published in August 1852, “A Sportsman's Sketches” captivated Turgenev's friends with a surprisingly fresh, intoxicating, unexpected discovery of deep Russia.

Orest Miller in his study "Russian Writers after Gogol" (1886) noted that initially many were perplexed how the censorship missed the “A Sportsman's Sketches” the general meaning of which boiled down to the denial of serfdom. “This fatal general meaning”, - emphasizes Miller, “Turgenev discovered back in the forties of the XIX century, because before that our literature, represented by its large representatives, somehow managed to remain indifferent to all this. It is known that Pushkin hardly approached the people from this side. Even Gogol pointed out the ulcer of serfdom only indirectly".

“A Sportsman's Sketches” finally consolidated Turgenev's literary glory, and not only in his homeland.

"With Turgenev, a turn in the attitude of Western European writers and society towards Russian literature is sharply marked", - wrote Professor Grigory Alexandrovsky in his published lectures "Readings on the latest Russian literature" (1906), presented on the Presidential Library’s portal. But Pushkin and Lermontov lost a lot when translating their poems into another language. “It was different with Turgenev. Brilliant art form, diverse, lively content, warmed by the soft light of high humane ideas ... immediately put him on a high pedestal in Western Europe. <...> Writers such as Maupassant, Zola, Flaubert, Goncourt have developed their aesthetic views ... largely under the influence of conversations with Turgenev and his works, - continues Aleksandrovsky.

"Fathers and Sons", "Rudin", "Asya" - each new piece by Turgenev became an era and caused heated controversy in the press.

“There is a lot in Rudin's character that reminds him of Turgenev himself”, - writes Evgeny Solovyov in “Ivan Turgenev" - Undoubted chivalry and not particularly high vanity, idealism and a penchant for melancholy, a huge mind and a broken will - isn't this the author of “Fathers and Sons”?"

Alexander Smirnov makes his conclusion on this matter in the article “Ivan Turgenev"...His sadness was a triple sadness - a patriot, a pessimist and a man who kept in his heart an ardent love for man”. Nikolai Plissky in his biographical sketch "Ivan Sergeevich Turgenev" summarizes: "Although Turgenev was a "Westerner", but this did not prevent him from being truly Russian, more than many of our compatriots who did not travel outside Russia..."