The Presidential Library’s rare materials illustrate Nikolai Nekrasov

“...It is unlikely that any of our great talents aroused in the mass of the reading public so many contradictory interpretations both during his lifetime and after his death”, - wrote literary historian Pyotr Boborykin in the article “Nikolai Alekseevich Nekrasov” published in the Nablyudatel magazine in April 1882.

The sources available in the electronic collections and on the Presidential Library’s portal will help to understand the contradictions of the complex personality of one of the most famous Russian poets, who celebrates his 199th birthday on December 10, 2020, to understand the originality of his oeuvre and the specifics of many years of editorial activity. For example, the textbook Readings on the latest Russian literature (1906) by Professor Grigory Alexandrovsky; the documentary film The hunting lodge of Nikolai Nekrasov, as well as the abstracts of dissertations - Dynamic aspects of the plot in the poem by Nikolai Nekrasov “Who Can Live Happy in Russia” (2014) by Ekaterina Sazhenina, etc. The greatest value and interest are the writer's publications in the Sovremennik magazine published by him and the memoirs of people who knew him personally: an article by the writer and critic Pavel Kovalevsky Meetings on the Life’s Journey. Nikolai Alekseevich Nekrasov (1910), notes by journalist Grigory Eliseev Nekrasov and Saltykov (1893), the book of the famous lawyer Anatoly Koni 1821-1921. Nekrasov. Dostoevsky. Based on personal memories (1921).

These materials illustrate how difficult the childhood and youth of Nikolai Nekrasov were.

When Nekrasov entered the philological faculty of St. Petersburg University as a volunteer, abandoning his military career, his angry father deprived him of material support. The poet's own testimony about this time is cited by Aleksandrovsky: “Exactly three years ... I felt constantly, every day, hungry. More than once it came to the point that I went to a restaurant on Morskaya Street, where they were allowed to read newspapers, even without asking myself anything: you would take, for show, a newspaper, and you would move a plate of bread to yourself and eat”. Pavel Kovalevsky recalled how he met “Nekrasov on Nevsky Prospekt, trembling in deep autumn in a light coat and unreliable boots, I remember, even in a straw hat from a crowded market…”.

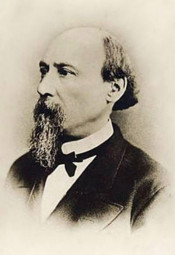

Nekrasov’s casual friends in their memoirs describe his appearance, character and habits, preserving the appearance of a poet for posterity. “...Of medium height, thin, with a pointed dark beard on a painful yellow face, with brown, not without guile eyes. As he walked, he leaned forward a little, especially a dry neck, and his head leaned back and swayed slightly”, - Kovalevsky described him like that. Pyotr Boborykin tried to define the "everyday type" of Nekrasov as "a typical person who developed in the environment of a landowner's life in Volga Region."

Contemporaries highly appreciated the editorial activity of Nikolai Nekrasov in the literary and socio-political magazine Sovremennik and the satirical supplement Svistok, as well as his leadership of another literary magazine Otechestvennye zapiski. Kovalevsky admitted: “I did not know the best editor like Nekrasov; we hardly even had another one like this. There were people who knew him, more educated...but no one was smarter, more perceptive and more skillful in dealing with writers and readers".

Boborykin expressed an interesting look at the relationship between poetic and journalistic principles in Nekrasov's work: “It seems to me that in him, as in a poet, two people consciously fought until his death: one was a poet, the other was an exposer of social ailments. Recently, the second has prevailed; but the first never - and fortunately - did not give up, did not want to shut up; and in his deathbed poems, poured out during the terrible suffering, he was resurrected anew.

When Nikolai Nekrasov passed away, Grigory Eliseev said about him: “I don’t know a single person who worked so hard and provided so many services to Russian literature as he did”.