Yesenin through his friends’ eyes in the Presidential Library stock

October 3, 2017, marks the 122nd anniversary of the birth of the great Russian poet Sergei Yesenin (1895-1925). There is a number of dedicated to the poet materials in the Presidential Library electronic stock, including the books, set of postcards with photographs with the poet, Sergei Alexandrovich Yesenin in the dialogue of cultures public video lecturing, scientific researches dedicated to author’s creative works, and most importantly — the memories of people from Yesenin's closest surrounding. They found in the poet a seeker, suffering from loneliness in the Moscow vanity and reaching the heights of his creative expertise.

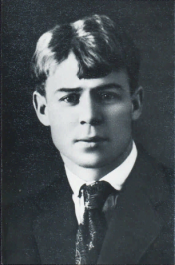

“Yesenin is imprinted in everyone's memory, almost stamped in it, with his blue eyes, a curly golden head, a faraway smile; and sometimes in the view of many — as a sort of prankster, <…> throwing into the crowded room brilliant words of his poems,” — a journalist, who worked in the newspapers Pravda and Izvestia (News of the Central Executive Committee of the Soviets of Working and Military Deputies), and Esenin's closest friend Sofia Vinogradskaya writes in her memoirs How has Yesenin been of 1926. Her memoirs, according to literary critic Valentina Kuznetsova, “in the extensive memoir literature about the poet are a kind of beacon.”

It was impossible not loving him. Yesenin had a colossal charm of on open, deeply original person, who was totally involved in conversation with his company. And only close friends knew that the poet’s excitement was sometimes intentional, and his natural artistry complied with special purpose.

A close friend of the poet Anatoly Mariengof in his book Memories of Yesenin (1926) describes how a peasant’s son with an objective to conquer the capital and deliberately “getting lost” in luxurious living rooms, taught his friend how to live: “It will be hard for you, Tolya, in lacquered shoos and with a exact a hair-to-hair part. How can you be without some poetic absent-mindedness? Are they flung out of space in their trousers from under the iron”!

About his “entry into literature” Yesenin had been reasoning frankly: “It has to be operated smoothly, bro. I thought, let everyone think: this is me who has introduced him into Russian literature. So, has Gorodetsky introduced? Yes, he has. Klyuyev introduced? Yes, he has. Sologub and Chebotarevskaya? Yes, they have. In a word: Merezhkovsky and Gippius, and Blok, and Rurik Ivnev… I really approached him first among the poets — he curved, I remember, his lorgnette down on me, and before I had time to read the twelve line verse, he began with his thin voice: “Oh, how fabulous! Ah, how ingenious! Oh…” and, grabbing my hand arm-in-arm, pulled me from celebrity to celebrity. <…> As for me, I’m a shy, one might say, shyer. From each praise I’m blushing like a girl, not looking at anyone because of such shyness…”

So, a loud metropolitan carousel rolled around: “Around him always was a crowd of people, among whom he was the noisiest, the most crouching, — according the book of Vinogradskaya. “And it's not that he filled the entire place with his noise, he set the place and its guests in motion, making them to live the same life with him. Wherever he was, everything lived for him. <…> It was possible to talk to Yesenin endlessly. He was inexhaustible, lively, interesting in his conversations, words, political arguments, sometimes full of childlike naivety, surprising, but cute misunderstanding of the utmost elementary things in politics. <…> “But what is “Capital” — an accounting,” — he would say. And a friendly laugh serves him an answer, while he himself, with boyish eagerness, looks at everyone looking like a lesser who just made the elders laugh.”

The friends at the same time knew what was the main thing in the life of the poet, from which he does not sleep at night. “The days of endless noise, din and music were changing by the days of work on the verse, — continues Vinogradskaya. — And then there were the days of melancholy, when all the colors paled in his eyes, and his own eyes blanched, fading gray from the blue.”

Talent, as is known, is a heavy burden and a great responsibility, because it is a “mission” given from above. Not everyone cope with this burden. It happens that there is a kind of “professional burnout” and, unfortunately, the closest to Yesenin people have noticed that in him. And he himself understood this more sharply than others when he wrote a farewell poem to Anatoly Mariengof:

At certain time, in certain year,

Perhaps, we’ll come across again…

I'm scared — my soul will also go somewhere

As youth and love just always pass away.

“The main in Esenin: the fear of loneliness. As for his last days in the Angleterre, he fled from his room, sat alone in the lobby, until the liquid winter dawn, knocked late at night at the door of the Ustinov room, begging him to let him in,” — Mariengof remembered already after Esenin's death in Angleterre's room.

Those who would like to know more about Yesenin's life will also be interested in electronic copies of photographic postcards that have captured the poet in different years. In addition to well-known official images, some family photographs are among them, in particular: Yesenin in childhood, with his parents, sisters, friends and colleagues, while serving on a medical train during the First World War. Sergei Yesenin, as a son, was carried deeply in his heart his native place — Ryazan village of Konstantinovo and could unexpectedly to go home in any situation. After the revolution, he attentively watched for collectivization and was hurt when faced the facts of violation of the interests of fellow villagers. “He loved the peasant in himself and bore it proudly,” — Mariengof wrote.

And, perhaps, because of this “ethnic mark” it was Sergey Yesenin who mentally embodied this image of forbidden, countryside Russia in the poetry.

“Since the time of Koltsov, the Russian land did not produce anything more native, natural, appropriate and tribal than Sergei Yesenin, giving him to his time with incomparable freedom and without burdening this gift with weighing a sixteen hundred kilograms painstaking of populist doctrine, — Boris Pasternak wrote in his essay on “People and Positions.” — At the same time Yesenin was a living, beating clod of the artistry, which we call after Pushkin the highest Mozart principle, the Mozart nature… The most precious in him is the imagery of native landscape, all wooded, the Central Russian, the Ryazan one, portrayed with such stunning freshness, like when he has gotten to know it in his childhood.”