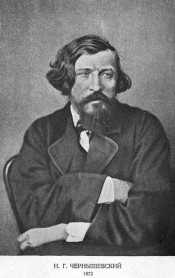

The identity and deeds of Nikolay Chernyshevsky

“I don’t have a single drop of artistic talent… I write novels, similarly to that workman hitting rocks on the highway”, Nikolay Chernyshevsky said about himself. Lenin called him a “great Russian writer”, “revolutionary democrat”, “genius visionary”. For contemporary readers, he is a man schematically depicted by Soviet textbooks as a revolutionary-minded person, who asked an “eternal” question in his most famous work – What Is to Be Done?. To it, he even tried to give an answer.

So who was Nikolay Chernyshevsky? How did his contemporaries view him? Rare and now hardly available in printed form materials, digital copies from the Presidential Library’s collections will help to answer these questions.

Nikolay Chernyshevsky was born in Saratov on July 24, 1828 in the family of a priest. The magazine Russian Antiquity (1912) states that the older Chernyshevsky got, the bigger was his passion for reading. He always preferred books to games.

After getting home-schooled under the supervision of his father, Chernyshevsky entered the Saratov Theological Seminary and actively engaged in self-education – he studied history, geography, theory of literature and several foreign languages. During those years, he was interested in the works of classics of German philosophy, English political economy, French utopian socialism, and Russian thinkers and public figures, primarily Belinsky and Herzen. In the seminary records of 1843, he was described as a person “of great abilities, zealous diligence, quite modest behavior”.

In 1846, Chernyshevsky entered the historical and philological department of the Saint Petersburg University, graduated, returned to the homeland to the joy of his parents and became a literature teacher in Saratov gymnasium.

The magazine Russian Antiquity features the following interesting facts.

A young man had a christening party. There were many guests, including Chernyshevsky and his parents. The guests started laughing at him, as he didn’t play any games, didn’t talk, didn’t dance. What’s the point of his knowledge, if he can’t function in a society? He should have become a monk… To which his father replied that he doesn’t talk, as there’s nothing to talk about, but if he did, people wouldn’t say those things.

And soon, he really did talk... The following story happened. Once, Nikolay was visiting a counselor. A woman was playing the piano, guests were listening nearby. One of the guests quietly asked Chernyshevsky something. He started talking, and everyone, one by one, surrounded him to listen to his answers instead of the piano. When Chernyshevsky finished his speech, someone started clapping and everyone joined in. “It’s good to listen to smart people”, they said to each other. “When he (Chernyshevsky) has guests, everyone talks about his intelligence, instead of wasting their time drinking”, a contemporary recalled. “He was a man of a true Christian life”, someone else sad, adding that people “slandered him out of spite” and exiled to Siberia.

Meanwhile, rumors began to spread in the gymnasium that Russian literature wasn’t the only thing Nikolay Chernyshevsky taught. After his lessons, students began to seriously ponder in their parents’ homes, for example, about the irrelevance of the post…

In 1853, Chernyshevsky got married and moved back to Petersburg, where he became a teacher in the Second Cadet Corps. At the same time, his literary and public career began. He collaborated with the newspaper Sankt-Peterburgskiye Vedomosti and the magazine Otechestvennye Zapiski. In the beginning of 1854, Nikolay became an employee in the magazine Sovremennik, where he soon took a leading post alongside Nekrasov and Dobrolyubov.

Physically weak and unhealthy, Chernyshevsky managed to transform Sovremennik into the tribune of revolutionary democracy just by an effort of will. Every step of his, according to Vasily Rozanov, was covered with “concern for the fatherland”, but to the police it looked like a preparation for the “outrage against the existing system”. He actively participated in the discussion of the upcoming peasant reform, speaking for the revolutionary-democratic party. Soon, the political ideas of Chernyshevsky put him alongside other ideological inspirers of the emerging Russian socialism and populism.

In the summer of 1862, he was arrested and put into solitary confinement in the Alexeyevsky Ravelin of the Peter and Paul Fortress. Readers can learn about the trial through the book of historian of Russian journalism Mikhail Lemke Political trials of M. I. Mikhailov, D. I. Pisarev and N. G. Chernyshevsky: (based on unpublished documents) (1907), available on the Presidential Library’s portal. According to the evidence, Chernyshevsky’s wife shared his views and helped him numerous times. Until the sentence announcement, he was put in the Peter and Paul Fortress, where he wrote to his wife on October 5, 1862: “…Our life belongs to history, centuries will pass, but our names will still be endearing to people…”

In solitary confinement, Chernyshevsky wrote over 200 author’s sheets of various compositions, including his most famous work – the novel What Is to Be Done?.

Interestingly, the book might have not existed. Nekrasov was the one taking the pile of papers featuring a manuscript of the future novel from the Peter and Paul Fortress. For safety, he tied it up with a rope, but eventually didn’t notice how he dropped the pile in the snow. To find the manuscript, an advertisement was published in the newspaper. Luckily, the papers were found, and the finder received 50 rubles in silver from Nekrasov.

Censors only saw the novel as a romantic story, and it was published in Sovremennik in 1863. After the novel’s release, they realized their mistake, but it was too late. Even though the magazine’s issues featuring the novel were banned, the text already was rewritten by hand and passed from one reader to another.

According to the historian of Russian literature Alexander Skabichevsky, the novel’s influence was colossal. It put all the main intelligentsia on the path of socialism. Production and consumption associations, workshops, tailor shops, cobbler shops, bookbinding shops, launderettes, communes for dormitories, etc. began to open everywhere.

The book was banned until 1905.

In February, 1864 Chernyshevsky was sentenced to 7 years of hard labor and permanent living in Siberia. Before that, the civil execution ceremony took place. Nevertheless, Chernyshevsky was not alone anymore. He was brought to his knees (it happened on Mytninsky Square, where the Chernyshevsky Garden is currently located), the peaked cap was thrown off his head, and the executioner broke a rapier above the head of the “state criminal”. In this moment, flowers were thrown from the crowd to the convicted man. The youth accompanied their teacher shouting “Goodbye!”…

At the katorga and after, Nikolay Chernyshevsky continued his literary activity, but none of his works reached the level of success of What Is to Be Done?.

In the summer of 1889, Chernyshevsky returned to Saratov. Unfortunately, just three months later, he got sick with malaria and couldn’t recover. He died at the age of 61 on October 29 (17), 1889 and was buried in his homeland.